“Things were the way they were.”

“The sit-in phase began on February 1, 1960, when four black college students in Greensboro, North Carolina, decided they had had enough of segregation…. When they went down to the local Woolworth’s store and sat in the whites-only section of the lunch counter, they sparked a nationwide student movement in support of better treatment of blacks in American society.”[1] So writes M.J. O’Brien in his book We Shall Not Be Moved: The Jackson Woolworth’s Sit-In and the Movement It Inspired. Indeed, the movement was nationwide, in the sense that the Greensboro sit-ins inspired similar protests in multiple states, including the most dramatic series of sit-ins in Jackson, Mississippi.

However, it was not all-encompassing. Modern readers should be careful not to infer from statements like this that all, or even a large portion of, black students across the nation participated in the movement. Even in Greensboro itself, there was a large segment of black students who had no interest in doing so. While many young Americans, both black and white, were inspired to take up the cause of fighting racial injustice, there also lived a less well-known, less vocal set of young Americans who made progress towards the same end, albeit unknowingly. Their eyes were undoubtedly fixed on a prize of some sort, but their actions were less publicized than those involved in direct protest. And while a modern observer might presume to speculate that their non-involvement made them passive, or even complicit, in the oppression of their fellow African-Americans, the impact of their experiences on the progression of civil rights should be celebrated rather than dismissed. The history of this movement benefits from an understanding of the non-participants’ experiences as well.

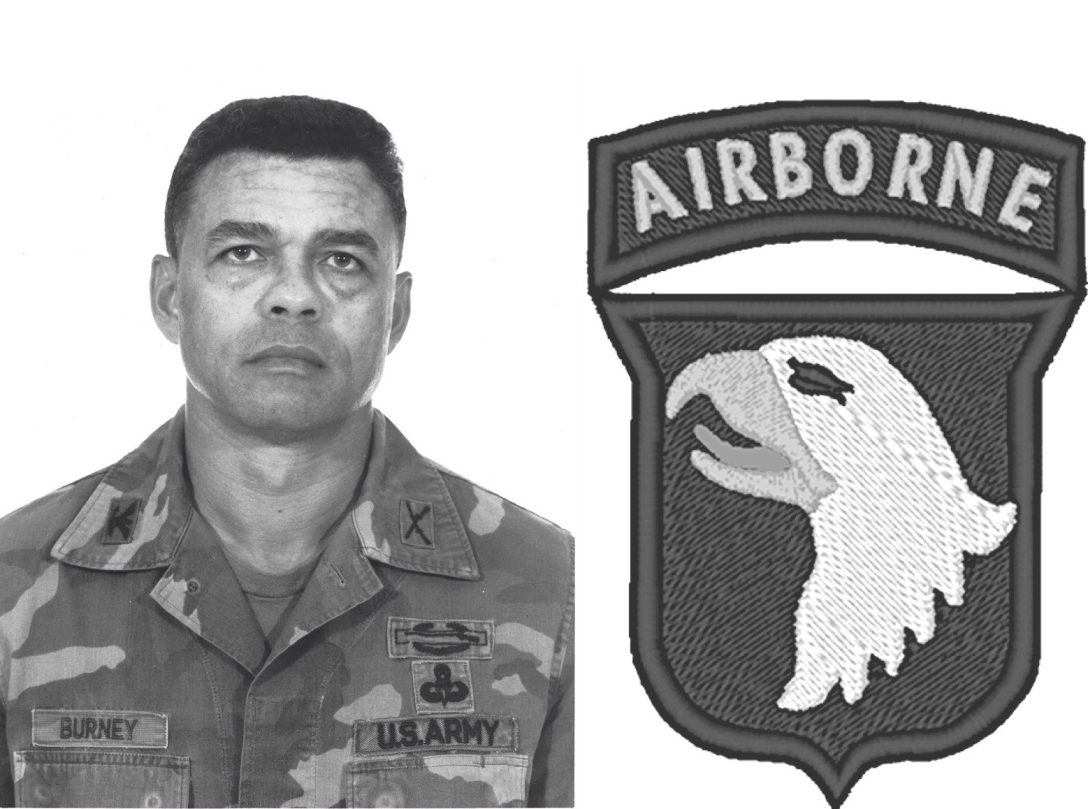

About a year after the first wave of Greensboro sit-ins, Linwood Earl Burney, my uncle, arrived for his freshman year at North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University (A&T). Lin’s parents drove him the 170 miles from Ayden, North Carolina where he had grown up working on the family farm. It was the farthest he’d ever been from home. Growing up, Lin didn’t know much about segregation or racial division; he says he lived a “sheltered life.”[2] His parents, he knew, were beneficiaries of the Reconstruction period, when there were “the carpetbaggers who came down and gave everybody a hundred acres.” But in their rural area, there was no oppression and everyone was poor. Or, as a modern sociologist might explain, everyone was oppressed. The distinction made no difference to Lin and his family.

As Lin and his parents drove into Greensboro that day in the fall of 1961, he remembers seeing some things that reminded him of “blatant [racial] division.” He also remembers not dwelling on it very much. Arriving at A&T was a “total eye-opening experience” for him not because it brought about a new awareness of racial injustice, but simply because it was different from his rural hometown. Like most college students leaving home, he gained new perspective, saw new things, and met new people. He found new opportunities as well. With dreams of becoming an Army officer, he enrolled in the Reserve Officer Training Corps at A&T and quickly got to work.

The Greensboro sit-ins of the year prior had been an important and relatively easy victory for the broader civil rights movement. “Whereas other cities sometimes desegregated their lunch counters only after protests lasting a year or more, the relative rapidity with which prominent economic actors and public officials in Greensboro accepted the necessity of a brokered settlement is telling,” writes Joseph E. Luders in The Civil Rights Movement and the Logic of Social Change. Luders describes Greensboro as a place where, due to its industry patterns, there was no “compelling interest in the defense of Jim Crow.”[3] Because the white residents of Greensboro had not experienced large-scale civil rights protests until this time, their efforts at “counter-mobilization” against integration were weak and ineffective. Thus, for a southern city in the mid-20th century, Greensboro’s enforcement of racial discrimination lacked the harsher or more violent elements that characterized Jim Crow in Selma or Birmingham.

Lin’s re-telling of his experience there aligns with this assessment. Because A&T was an all-black school, Lin says he didn’t experience the negative effects of segregation on campus, and saw only intermittent reminders of discrimination out in town. He told me about a time that he and some friends went out to the movie theater, and one of them decided that they would sit “downstairs,” in the whites-only section. The friend led the way in to the downstairs seating area and yelled back to the group, “Hey guys, I’m in!” This fellow, Lin recalls, was already so light-skinned “he could have been Caucasian,” so it was no surprise that he had not been stopped. Immediately upon uttering these words, however, he was removed by a security guard and sent to rejoin his friends. Lin remembers this as a hilarious instance, not something particularly “earth-shattering.”[4] During our conversation, he tried to remember more negative things that happened to him but genuinely could not. Lin told me he and his friends knew that “things were the way they were,” – racial discrimination was simply a part of life in North Carolina, and not worth becoming overly concerned about.

One day when he was hungry, Lin ventured down to the basement of one of the A&T buildings. Thinking that he had stumbled on free drinks and sandwiches, he instead found Julian Bond speaking to a group of students. Uninterested, he left the venue. He told me that Bond and other civil rights leaders spoke on multiple occasions during his time at A&T, but that neither he nor the other guys in his social circle were particularly interested in hearing them. They were focused on working hard, earning their degrees, and getting jobs. As a ROTC cadet, Lin said he heard his fair share of “silliness,” which included derogatory language and off-color jokes – the worst of which came from within his group of friends. This did not, in his recollection, have any significant impact on him or his development.

After the sit-ins, the next most notable event in Greensboro’s civil rights history occurred in 1963. In his book Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina and the Black Struggle for Freedom, William Chafe describes a massive political and social struggle that “rocked” the city:

“For eighteen nights, black marchers numbering more than 2000 assaulted the bastions of segregation in the city’s central business district. At one point 1400 blacks, most of them college students and teenagers from area high schools, occupied Greensboro’s jails. The demonstrations shattered white Greensboro’s confident self-image, shook the city’s social and political institutions to their foundations, and emphasized as never before the conflict between racial justice and North Carolina’s progressive mystique.”[5]

In a gripping chapter of the book, Chafe describes the intellectual and political war that raged, pitting prominent civil rights leaders against powerful business interests. “If [Tony] Stanley was the intellectual strategist and [William] Thomas the field general, Jesse Jackson was the hero who led the troops into battle and inspired the rank and file,” Chafe says.[6] All of these men, it is worth noting, were either students or employees of A&T, where Lin went to school. Based on dramatic descriptions like Chafe’s, one might assume that the entire African-American population of Greensboro was swept up in a raging fight over economic racism. Lin would disagree. Even as a black college student attending the same school as the key players, he has little to no recollection of the events that took place there – the “stuff you probably read about in books.” There was a certain type of people, he said, who were involved in “all that,” but he and his friends simply were not interested.

In our conversation, Lin expressed mild contempt for his contemporaries who continue to portray themselves as “victims” of the time period. He said he is constantly “astounded by how people exaggerate… and overblow the details of what went on.” Those people are the same people who tend to “make a boogeyman out of almost anything — you gotta let crap like that go.” Sure, there was oppression and discrimination, he told me, but “you gotta put it over here some place where it doesn’t impede you from accomplishing your goals.”[7] I asked him if being in the military had influenced his perspective on that issue, and he told me it certainly had. For all its imperfections, the military was one of the first drivers of merit-based recognition for black people in American society.[8] Lin benefited from the relatively early integration of the U.S. Army, and his early introduction to the armed forces’ meritocracy shaped not only his career opportunities but his entire perspective on life and society as well.

Based on Lin’s story, it is easy to see why his views on American opportunity do not evince a pronounced emphasis on systemic racism and institutionalized oppression. This does not make his views any less valid or important as a primary source. One might call Lin naïve, or try to tell him that he is not sufficiently educated about the ways in which African-Americans in other economic sectors were prevented from advancing in society the same way he eventually did, or the ways in which the history of slavery and oppression still affect people today. But as a African-American person living in the time period, his experience lends important insight into how some people made progress.

Evaluating the 1960s as a whole, Lin readily admits that social change took place for African-Americans, but is hesitant to assign all the credit to the civil rights movement and its leadership. He says he has no personal memory of the March on Washington or of hearing about Dr. Martin Luther King’s most famous speech. Instead, he remembers the respect he and other black soldiers earned in Vietnam serving alongside (and in command of) white soldiers, proving with their actions the equal humanity on which Dr. King and other leaders waxed so eloquently. He says he’s not sure whether social change happened because of “all that stuff” or because people just eventually realized “that if you were qualified to do the job, you should have the job.” He’s probably willing to admit that it was a little bit of both. Today, my Uncle Lin speaks with his own sense of well-earned pride and dignity – a gravitas earned through decades of honorable service and noble family life. Lin has lived not as a victim of injustice, but as someone who believed in the premise of American opportunity and worked to gain the social status he truly believed he could rightfully earn. If one were to ask Lin, “what did you do in the movement?” he would quickly respond, “nothing.”

But he would be wrong: during the waning days of the civil rights movement’s classical phase, 2nd Lieutenant Linwood Burney graduated from A&T and deployed to Vietnam as a commissioned officer of the United States Army. He was then entrusted with lives of American soldiers for the next quarter-century. In 1969, he led a company of the 101st Airborne Division through ten days of bloody fighting on Hamburger Hill.[9] In the years that followed, he rose to the rank of full colonel and commanded a brigade. Along the way, he earned his troops’ lifelong loyalty, playing an integral role in the changing narrative about African-Americans in society. “Once I kept them alive, they didn’t care what color I was,” he told me. These parts of Lin’s story demonstrate why modern observers should not be too eager to judge those who did not march or protest with Dr. King in the 1960s, or who do not now spend much time researching or speaking about the injustices of history. In the minds of thousands of both black and white soldiers in Vietnam and in later conflicts, Linwood Burney’s focused professionalism and service likely did as much or more to eradicate racial prejudice than the sit-ins, marches, and speeches back home. In a way that may befuddle the modern civil rights historian, this occurred precisely because of his refusal to acknowledge racial barriers as a substantive obstacle in his life story. “Things were the way they were,” Lin says, and he made the best of the way things were. In a sense, Lin’s success was its own form of rebellion.

Even a casual study of the 1960s demonstrates the necessity of direct civic action and the crucial role protests and speeches played in weakening America’s commitment to Jim Crow. Mass movements need social drivers, and there certainly were millions of Americans whose minds were changed by the courageous figures and dramatic events they saw on TV. In retrospect, however, it is hard to judge how effective the civil rights leaders’ efforts would have been had they not been coupled with the example of men who, with credibility and courage, proved with their lives that human dignity and equality are not just talking points or protest-starters, but values worth fighting and saving lives for. For every Martin Luther King, Jr. who decries evil in the public square, there lives somewhere a Lin Burney who lives with integrity and capitalizes on the opportunities he is given, thereby persuading his fellow men of the true value of social progress.

—

[1] M.J. O’Brien, We Shall Not Be Moved: The Jackson Woolworth’s Sit-In and the Movement It Inspired (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2013), 3-4

[2] Linwood Burney, interview by Thomas Krasnican, May 4, 2018

[3] Joseph E. Luders, The Civil Rights Movement and the Logic of Social Change (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 79

[4] Burney

[5] William H. Chafe, Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina and the Black Struggle for Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), 167

[6] Ibid., 175

[7] Burney

[8] Charles C. Moskos, Jr., “Racial Integration in the Armed Forces,” American Journal of Sociology 72, No. 2 (1966)

[9] Samuel Zaffiri, Hamburger Hill: The Brutal Battle for Dong Ap Bia (New York: Ballantine, 1988), 195

I served with Col. Burney in 2nd BDE 7th ID. He was a great commander.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had the honor of serving with Col Burney in the 2nd Bde, Ft Ord Ca. Colonel Burney forever changed our lives as he was a true professional who demanded nothing less than perfection; and for that many lives were saved when we were called into action. A true American in every sense of the word. Thank you much Sir.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was a Light Fighter in 2nd Brigade, Col Linwood Burney was an inspiration to every soldier in his command! He had more respect from his men and was a true leader in every respect. I’m a better person to have served with this man and I will never forget. Thank you

COLD STEEL

LikeLiked by 2 people

I had the honor of carrying his radio in Viet Nam for a short period of time…He left an impression…..

LikeLike

I served with Col Burney, in hq,hq batallion fort ord cali. in the

mid 80’s. The pt was called the “Burney burn-out”, if he was with us in the morning you knew you were going to run nine miles and definately get a hella work out. Ill never forget being in mop 4 gear with a radio in my hand and my m16 slung, trying to fix his como….i could tell there was something about him as a leader..

LikeLike

then LTC Burney was IG of the Berlin Brigade when I was a lieutenant there and went on to command 2-6 Infantry that had a race-based protection racket running in it. He earned the nickname Darth Vader cleaning it up. I later commanded a company in 2d Brigade of 7ID. He took command just as I was leaving. He commanded the Brigade during JUST CAUSE. I kept in contact with a lot of people there and I know he was highly regarded.

LikeLike

When LTC Burney was commander of 3/6 INF in Berlin, he was the man and the myth. Tough as nails but gave you ground if you knew your stuff. Never try to BS the man, he would catch it and toss ya over the Berlin Wall in a heart beat. No questions. He was hard as “teeth of beaver” and the BN would follow him to hell and back. Salute!

LikeLike

Totally agree with you John. Mike Brown Scouts CSC, 3/6 Inf.

LikeLike

The very mention of “Cold Steel” put a frown on the faces of soldiers of the 2Bde Light Fighters. But, what we came to understand was; it was the forging of the mental and physical spirit needed to be confident and persevere in combat. Burney led the Brigade with a relentless spirit, being every where at one time and leaving no detail unobserved. He demanded much from his Officers and Enlisted men all the while challenging you to succeed. It can be said that Burney did not “suffer a fool” and he let you know it. He worked and trained hard and expected you to do the same. Burney was a “leaders leader” in every since of the word. I developed a great respect for Burney as a leader and a man. I had the great honor to include Burney and his wife as Guests of Honour in my wedding ceremony. I am proud to have been a Light Fighter and served under this man

No photo description available.

LikeLiked by 1 person